Yoshimura history -31

Tamaki Serizawa (front row center) and Andrew Stroud (back row in racing suit) rode the water-cooled GSX-R750SP Superbike spec machine to an impressive 8th place finish at the 1995 Suzuka 8 Hours. Standing in the center, Naoe holds a portrait of her husband Pop, who passed away in March. On her right, their son Fujio also wears a peaceful expression. Photo courtesy of Yoshimura Archives

Yoshimura History #31: A New Era Dawns with the Shift to Water-cooled Engines

1992-1995: The GSX-R750W Arrives

In 1992, the Suzuki GSX-R750 finally received a water-cooled engine. The oil-cooled (“Air/Oil Cooled” to be precise) unit was groundbreaking at the time of its debut in 1985, but its seven-year run was certainly too long. Needless to say, direct rivals such as Honda’s VFR750F, VFR750R (RC30) and RVF750 (for TT-F1), Yamaha’s FZ750, FZR750, FZR750R (0W-01) and YZF750 (for TT-F1), and Kawasaki’s ZXR750 and ZXR-7 (for TT-F1) were already equipped with water-cooled engines. All of these bikes underwent frequent upgrades and evolution of not only their engines but also their chassis, making them ideal base models for TT-F1 as well as AMA & FIM Superbike racing.

The water-cooled engine of the new GSX-R750, Model Code GSX-R750W, did not have the forward-leaning cylinders that were gaining ground, but instead had an almost vertical layout like the oil-cooled predecessor, maintaining the exact same bore and stroke of 70mm x 48.7mm (749cc). Also, instead of the latest side-cam chain design, which allows for narrower engine widths and straighter intake ports, the conventional center cam-chain design was carried over. The frame also remained aluminum double-cradle, not aluminum twin-spar.

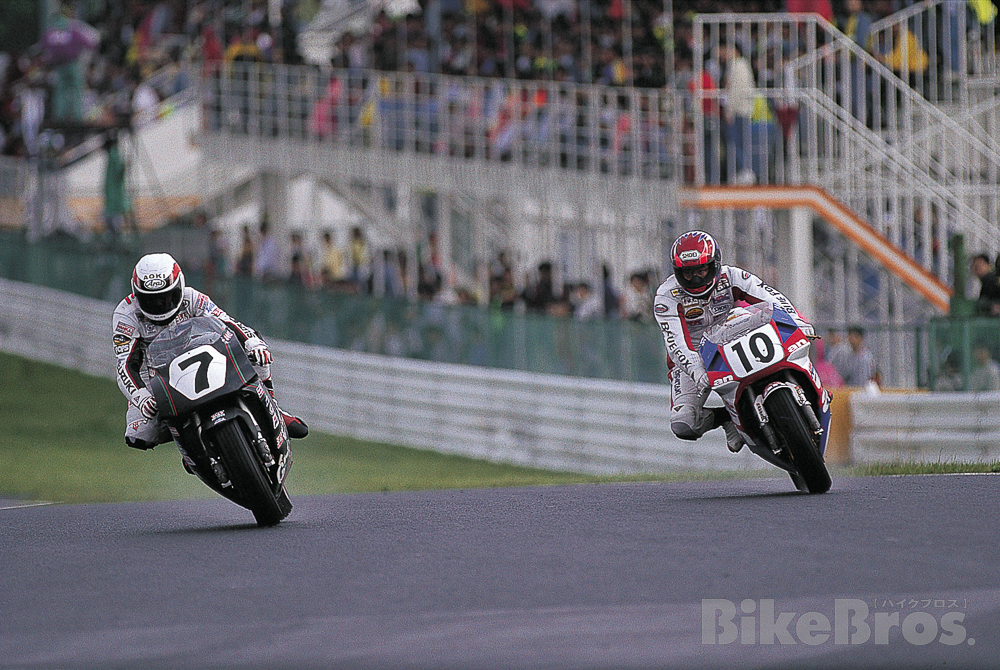

The #7 Aoki battles with the #10 Takeishi (Honda RVF750) at the 1st corner of Tsukuba in 1992. The water-cooled GSX-R750 was not as powerful as Honda V4, but it proved to be competitive enough on the short, rainy Tsukuba Circuit. Photo courtesy of Osamu Kidachi.

The GSX-R750W entered the 1992 FIM racing season, including All-Japan and endurance races, but because homologation was delayed a year for the AMA, Yoshimura had to enter the 1992 AMA Superbike Series with oil-cooled GSX-R750’s fitted with larger cooling fins, resembling those of air-cooled bikes. The result was a struggling race, and although David Sadowski did well to finish 4th at the Daytona 200-mile race, he ended up 12th in the ranking. Britt Turkington also finished in 6th place at best and 15th in the ranking.

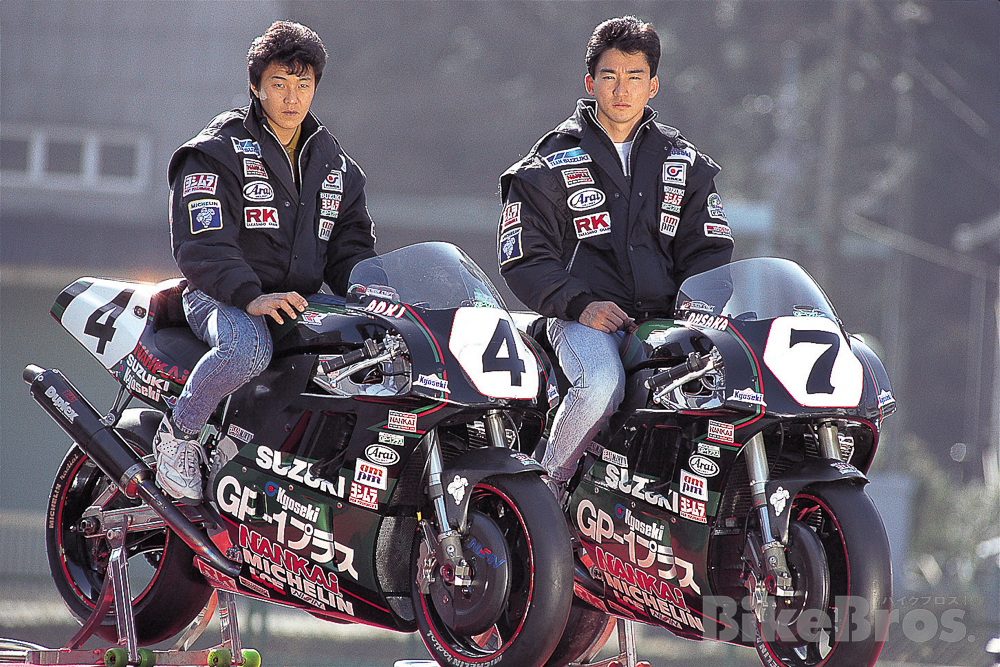

For the 12 rounds of the All-Japan TT-F1 Series, the team fielded Masanao Aoki (in his third year with Team Yoshimura and his second year in full TT-F1) and newcomer Kenji Osaka. The two were friends from Mirage Kanto, which is practically Yoshimura’s junior team. Since the International A-class TT-F3 was dropped from the 1992 calendar, all manufacturers were able to concentrate on TT-F1, making the class more intense. With the new water-cooled engine, power output of the GSX-R750W was higher than that of its predecessor, but still not as high as that of its rivals, namely the Honda RVF750 and the Kawasaki ZXR-7. However, the chassis for the TT-F1, still constructed by the Suzuki Factory, had an enlarged cross-section like a twin-spar frame, enhancing its rigidity.

#16 Kenji Osaka was with Yoshimura for two seasons. Prior to that, in 1990, he paired up with Masanao Aoki on a Yamaha FZR750R (0W-01) for the KISS Racing Team and finished 32nd. Then in 1992 and 1993, he again partnered with Aoki, this time with Team Yoshimura, and finished 5th in 1992 and 22nd in 1993. He later switched from being a motorcycle racer to a radio controlled car driver, and became a world champion in 2001. Photo courtesy of Osamu Kidachi.

Aoki and Osaka did their best under such circumstances. Aoki took pole position at Round 1 in Mine Circuit (the final race was cancelled due to rain), followed by a 3rd place podium finish at Round 2 in Tsukuba, 2nd at Round 3 in Sugo, 4th at Round 4 in Suzuka, and 3rd at Round 5 in Tsukuba. He was very close to winning the championship, but he lost his momentum from the middle rounds of the season, and although he finished 2nd in the final round at Tsukuba MFJ Grand Prix, he was unable to win the championship. In the ranking, he finished 4th, overcoming the inferiority of the GSX-R750W. Osaka also did well, with the best finish coming in 4th place, and the 7th in the ranking.

For the 1992 Suzuka 8H, Yoshimura fielded a two-bike team consisting of Aoki / Osaka and Peter Goddard / Michael Dawson. Aoki / Osaka with Ace #12 started the race from a good grid position by qualifying 2nd and finished in 5th place. Goddard and Dawson on #34 retired with engine trouble after about 3.5 hours.

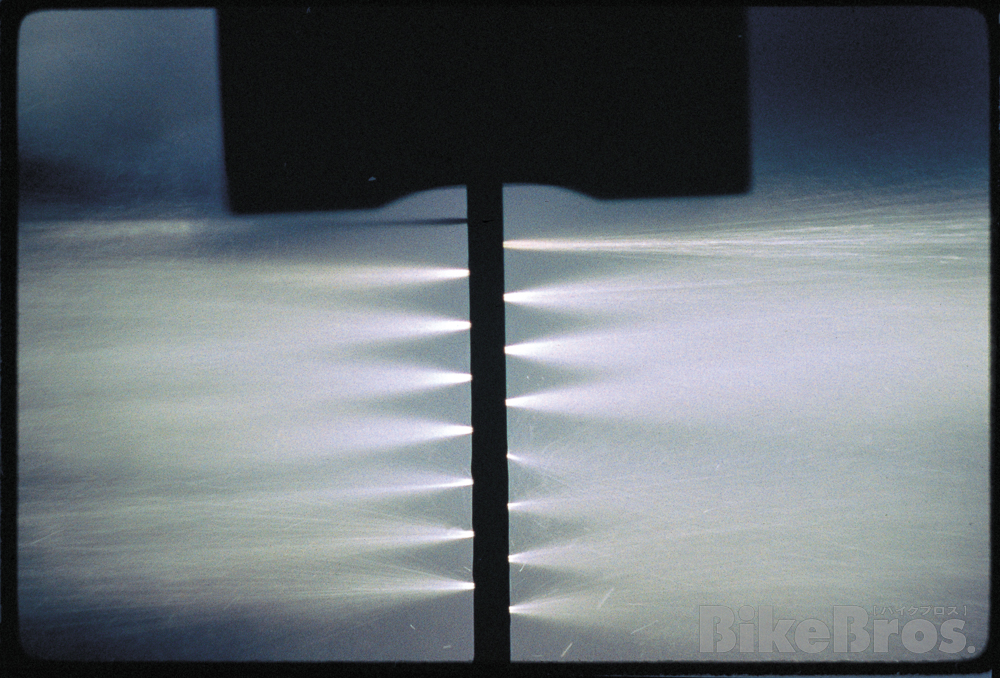

Yoshimura MJN (Multiple Jet Nozzle) carburetor in action. Fuel is injected from the holes lined up on both sides of the MJN, generating a white cloud across the carburetor throat. Atomization in reality is much more dynamic than the shown image. The diameter and interval of the nozzle hole varies in proportion to the position of throttle valve; the holes are smaller and closer together on the close (low rpm) side, and larger and further apart on the open (high rpm) side. Photo courtesy of Yoshimura Archives.

In 1992, a game-changing breakthrough came with the introduction of the Yoshimura MJN (Multiple Jet Nozzle), a carburetor component invented by Fujio that replaces the standard jet needle with a tube with a dozen or so side holes, through which the fuel sprays out. The MJN has the effect similar to having fuel injection built into the carburetor, providing significantly superior fuel atomization, which not only improves power and engine response, but also enables better fuel economy. In fact, in later years, the MJN was installed on many machines that competed in fuel efficiency races.

The development of the MJN was carried out over several seasons in actual competition by installing it in the magnesium-bodied Mikuni TMR40, a carburetor specially designed for factory machines, with riders such as Doug Polen and Aoki in charge of testing. Conversion kits for the Mikuni TM and BST (CV type) were introduced to the market first, and when the new Mikuni TMR racing carb replaced the TM in 1993, the Yoshimura TMR-MJN (TMR carb with the MJN pre-installed) became the standard, and eventually MJN became available for the Keihin FCR and CR Special as well.

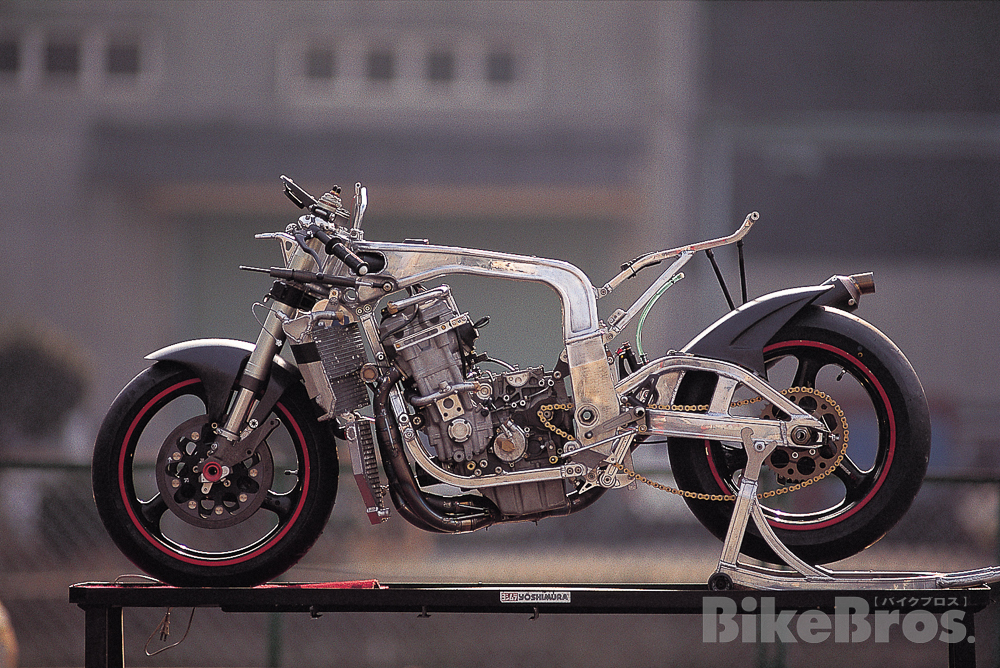

Until 1993, both the main frame and swingarm of the TT-F1 spec Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750 (including this GSX-R750W) were built at the Suzuki Headquarters. Note the ribbed main frame and machined swing arm pivots. Photo courtesy of Kenji Matsushima.

1993 was the final season for the All-Japan TT-F1 class, which limited engines to be based on production machines: 400-750cc for 4-stroke 3 & 4-cylinder engines, 550-1000cc for 4-stroke 2-cylinder engines, 200-375cc for force-inducted 4-stroke 4-cylinder engines, and 250-500cc for 2-strokes. It was the pinnacle class of the world’s major production motorcycle races, such as the All-Japan and the FIM Endurance World Championship (EWC), including the Suzuka 8-Hours. There were no restrictions on chassis and no weight requirements, so manufacturers were able to take full advantage of cutting-edge technology and lightweight materials. Some of the factory machines of this era, especially the sprint version, were so light that they weighed close to 130 kg. Even the endurance specs were usually in the 140 to the low 150 kg range.

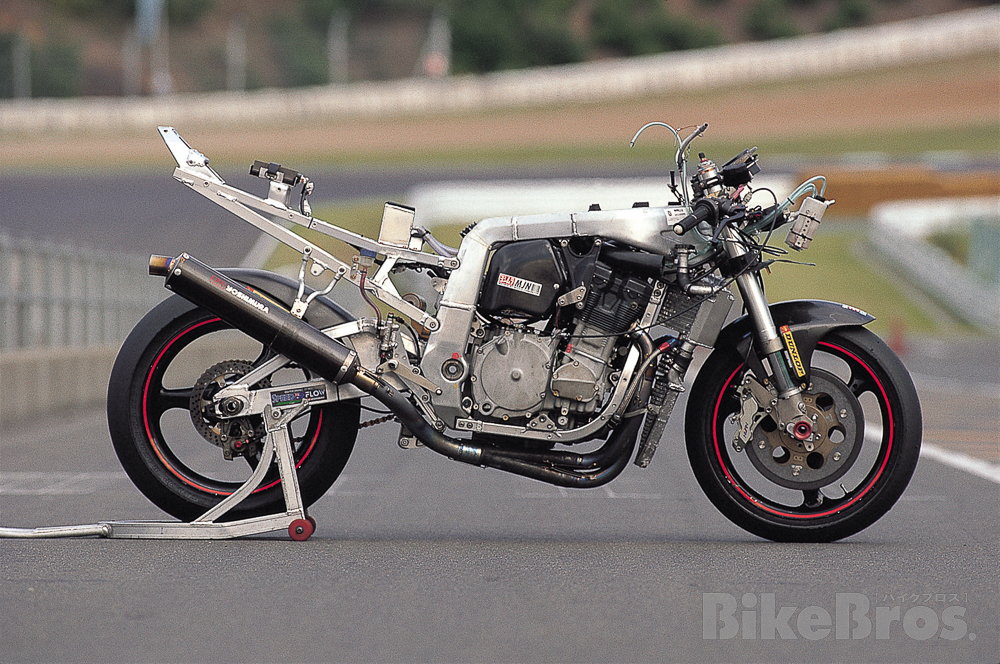

1994 All-Japan spec Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750W Superbike. Its main frame is stock but is reinforced. Interchangeable swingarm is made by Suzuki Headquarters. Front and rear suspensions are by Showa. Front brake features carbon discs (banned after the 1995 season and replaced by steel discs). Photo courtesy of Osamu Kidachi.

The pinnacle class of the All-Japan Road Race Championship was replaced by Superbike, which follows the FIM regulations, starting with the 1994 season. Superbikes are limited to 4- strokes only, with 4-cylinder engines ranging from 600 to 750 cc, 3-cylinder engines from 600 to 900 cc, and 2-cylinder engines from 750 to 1000 cc. Not only the engine but also the chassis was stock-based, with a minimum weight limit of 162 kg, which was considerably heavier than that of the TT-F1. This means that the potential of the base machine is the prime factor in Superbike racing.

Since the Suzuka 8 Hours was elevated to an FIM Endurance World Championship event in 1980 by conforming to TT-F1 regulations, it has been an even hotter battle of pride and honor among the four major manufacturers than ever before. In 1993, Yoshimura (Yoshimura Suzuki GP-1 Plus) entered the last Suzuka 8 Hours race to be held under TT-F1 regulations with two GSX-R750Ws, #12 Aoki / Osaka and #34 Dawson / Alex Vieira. Meanwhile, the factory teams were Suzuki (Lucky Strike Suzuki) with two GSX-R750Ws, HRC with four RVF750s (old and new models), Yamaha with three YZF750s (YZF750 & YZF750SP), and Kawasaki with two ZXR-7s. It may be an exaggeration to say that they were betting the fate of their company on the Suzuka 8H, but they certainly placed a near priority on winning the event. The Suzuka 8 Hours could be called the world’s top 4-stroke bike race, and some manufacturers even positioned the All-Japan races as mere “warm-up” for the Suzuka 8H.

A group photo with Fujio in the center, taken at the Yoshimura Japan Workshop just before the 1993 Suzuka 8 Hours. The #12 is for Aoki / Osaka, and the #34 is for Dawson / Vieira. The #4 seat cowls on the wall is for Aoki’s All-Japan machine. Photo courtesy of Takao Isobe.

In qualifying, Yoshimura #12 Aoki / Osaka placed 10th, while Suzuki Factory #10 Akira Yanagawa / Noriyasu Numata did well to secure 4th place.

The final race unfolded dramatically. First, Lucky Strike Suzuki #10 Yanagawa retired after just three laps due to a mechanical issue. Then, Eddie Lawson (with Satoshi Tsujimoto on Honda RVF750), who had been leading, crashed on the Reverse Bank –––– Turn 6, known as Gyaku Bank –––– during the final lap of the first stint after hitting oil. He restarted but dropped out of the top group. Next to crash was Mick Doohan (Honda RVF750). Concerns arose for his right leg, severely injured in 1992 (which led him to use a left-hand thumb control for the rear brake), but he managed to pick up his bike, restart, and return to the pits for repairs. Further setbacks for the Honda RVF squad came as the fastest Japanese team, Shinya Takeishi / Kenichiro Iwahashi, suffered repeated pit stops due to fuel system failure, dropping them out of contention for the win.

Yoshimura #12 saw Osaka and Aoki crash one after another. They restarted but finished 22nd. #34 Dawson / Vieira placed 10th. The last TT-F1 Suzuka 8H victory was achieved by Scott Russell / Aaron Slight on a trouble-free, crash-free ZXR-7, marking Kawasaki’s first Suzuka 8H win.

In the 1993 All-Japan Road Race Championships, Osaka ranked 6th and Aoki ranked 7th, with neither making it onto the podium.

For the 14th Suzuka 8 Hours (Round 3 of the World Endurance Championship), Yoshimura entered the race with #12 Aoki/Kipp and #45 Martin/Blair. #45 suffered a crash and fire with Martin, but returned to the race after major repairs in the pit. #12 also experienced a crash and fire with Kipp during the final stint, but restarted. #12 finished in 9th place, and #45 in 28th place, successfully completing the race.

Continuing from 1992, Aoki (left) and Osaka (right) teamed up to compete in the All-Japan Championship and Suzuka 8 Hours in 1993. Photo courtesy of Kenji Matsushima.

The Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R750W was finally entered into AMA racing in 1993. For Superbike, Thomas Stevens and Donald Jacks were entrusted with the new water-cooled machine. However, Jacks crashed and was injured at the season opener in Phoenix, ending his season. Ace rider Stevens finished as high as 4th and ended the season ranked 8th. The champion was Doug Polen on a FBF (Fast By Ferracci) Ducati.

Meanwhile, in the AMA 750 Supersport (Superstock class), Britt Turkington dominated aboard the GSX-R750W, winning four of ten races to claim the championship. He also performed exceptionally well in the AMA 600 Supersport, finishing 2nd in the standings aboard the water-cooled GSX-R600 (a scaled-down version of the 750).

Also, at the Daytona 200 (AMA Superbike Round 2), Suzuki Factory’s Yanagawa competed on a GSX-R750W. He showed the speed to take 3rd position at one point, but unfortunately retired on Lap 52 due to engine failure.

Yoshimura entered the newly established All-Japan Superbike class in 1994 with a two-rider lineup consisting of Nukumi (pictured) and Suzuki. The same duo also competed in the Suzuka 8H. The Superbike-spec GSX-750SP featured a special swingarm and linkage. Suspension was Showa front and rear, with front brakes sporting Nissin 6-Piston calipers and carbon discs. Photo courtesy of Osamu Kidachi.

Finally, in 1994, the pinnacle of world four-stroke production road racing was unified under Superbike. While the SBK (Superbike World Championship), AMA and All-Japan series have slightly different regulations, the fundamentals are the same. With the discontinuation of GP500, All-Japan’s top category, Superbike became the premier class, and manufacturers shifted their focus to Superbike.

Yoshimura entered the inaugural Superbike season in the All-Japan Championship with a new lineup featuring Yukio Nukumi and Makoto Suzuki. Their machines were the domestic model GSX-R750SP, a lighter version of the GSX-R750W. However, they struggled, barely managing single-digit finishes, and the championship ended with Nukumi ranked 15th and Suzuki ranked 19th.

Similarly in the EWC (FIM Endurance World Championship), Yoshimura entered the Suzuka 8 Hours for the first time under Superbike regulations with its usual two-bike lineup: #12 Nukumi / Suzuki and #34 Niall Mackenzie / Shawn Giles. The starting grid saw #34 Mackenzie / Giles on the 8th grid position and #12 Nukumi / Suzuki on the 18th grid position.

In the final race, a multi-bike crash involving the leading group occurred immediately after the start at the 12th corner (200R, known as Matchan Corner) on the West Course. The crash resulted in a major fire, prompting a red flag. After a lengthy interruption, the race restarted, in which Doug Polen / Aaron Slight (Honda RC45) defeated Scott Russell / Terry Rymer (Kawasaki ZXR750R) by 0.288 seconds. Typically, the winning bike makes 207-208 laps, but in this event, it was 183 laps. Yoshimura’s #Mackenzie / Giles finished 11th, while #12 Nukumi / Suzuki retired after 108 laps.

#11 Thomas Stevens attacking Daytona’s Turn 1 in 1995. After winning the AMA Superbike Championship on a Yamaha in 1991, Stevens rode for Yoshimura for three years from 1993 to 1995. Photo courtesy of Tomoya Ishibashi.

Yoshimura entered the 1994 AMA Superbike series with three riders: Thomas Stevens finished 9th in the standings, Tom Kipp 12th, and Donald Jacks 17th. In the AMA 750 Supersport, Kipp won five of ten races to claim the championship, while Turkington secured two wins and finished second in the standings, as the Yoshimura team dominated the series. This marked their second consecutive title in the 750 Supersport class.

Then, on March 29, 1995, Hideo “Pop” Yoshimura passed away. He was 73. Though he had stepped back from the forefront of tuning in the late 1980s, he remained the symbol and spiritual pillar of Yoshimura. Since founding Yoshimura Motors, the predecessor to Yoshimura, in 1954, he had been a master engineer with divine touch —- people called it God’s Hands —- who continuously brought numerous innovations to enhance the output of 4-stroke engines, including 4-into-1 exhaust systems, high-lift camshafts, and cylinder head tuning.

Amidst this, Yoshimura scaled down its All-Japan team and entered just one bike. The team started with GP rider Kevin Magee, who also had a Suzuka 8 Hours victory to his name. However, starting from Round 3 at Fuji Speedway, he was replaced by former Motocross racer Tamaki Serizawa. Born in 1972, Serizawa was a gifted talent who surprisingly advanced to MX International A-class while still in high school, before switching to road racing in 1992. Magee was ranked 26th, while Serizawa was ranked 18th.

At the 1995 Suzuka 8 Hours, Yoshimura continued with a single-bike entry, and despite the water-cooled GSX-R still not being particularly high-performing at that point, they put up a good race. #12 Serizawa / Andrew Stroud (Yoshimura Suzuki GP-1 Plus) started from 15th on the grid and finished an impressive 8th in the race. Also, Fred Merkel, who was active in AMA races as a contract rider for US Yoshimura, competed with Peter Goddard for the Suzuki factory team (Lucky Strike Suzuki) and finished 6th in the race.

#27 Fred Merkel approaching Daytona’s Turn 1 in 1995. Merkel’s relationship with Yoshimura dates back to 1982, when he rode two races on a GSX1000 Katana during the AMA off-season. He was the AMA Superbike Champion from 1984 to 1986 and the SBK World Champion in 1988 and 1989. Photo courtesy of Tomoya Ishibashi.

At the 1995 AMA Superbike season opener, the Daytona 200, Stevens got off to a promising start by finishing 3rd and stepping onto Victory Lane (Daytona’s uniquely flat podium). Merkel finished 8th, and Jacks was 9th. At Round 4 at Mid-Ohio, Merkel took the 3rd-place podium. Ultimately, in the championship standings, Merkel finished 4th, Stevens 7th, and Jacks 14th. Sadly, Jacks passed away in a traffic accident on June 29th, just after Round 6, at the very young age of 25. In the 750 Supersport class, Merkel won 7 of the 10 races but narrowly finished 2nd overall.

The water-cooled GSX-R750 may not have been successful in Superbike racing, but it did leave a lasting mark on the era.

Victory Lane at the 1995 Daytona 200. From left: 3rd Thomas Stevens (Yoshimura Suzuki), winner Scott Russell (Muzzy Kawasaki), 2nd Carl Fogarty (Ducati). Photo courtesy of Tomoya Ishibashi

Stories and photos supplied by Yoshimura Japan / Osamu Kidachi / Takao Isobe / Tomoya Ishibashi, Kenji Matsushima

Written by Tomoya Ishibashi

Edited by Bike Bros Magazines

Published on January 27, 2025

[ Japanese Page ]